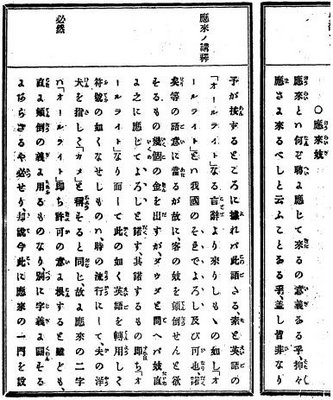

I received a lot of guidance from observing Mori Ōgai’s [orthographic] method, and tried as best I could to learn from it and carry it out myself. And certainly even today most of my writing reveals his influence in this respect, but nevertheless I frequently find myself questioning my judgment, so that I end up just as confused as ever. But this is not necessarily just a problem of my own ignorance and laziness. I don’t want to go on and on, so I’ll refrain from giving a lot of examples, but to put it simply, no matter what methodology one chooses to follow,

ateji and kana usage nevertheless remain persistent problems. If, for instance, one were to follow Ōgai’s method exactly, one would have to write hitoe [under-robe] as 一と重 rather than 単衣, awase [lined kimono] as 合わせ rather than 袷, and uchi [home] as 内 rather than 家, but I can’t bring myself to take things that far. Anyway,

kun originally took the meaning of a Chinese character and read that character with a Japanese word which fit with that meaning, and so when people today read 卓子 as テーブル [table] or 乗合自動車 as バス [bus], nothing’s really changed. And if that’s the case, then there’s no reason to say that 家 can’t be read any way but “ie,” or that recently invented readings aren’t genuine. One can even accept that hitoe and yukata are just the readings that have been given to the compounds 単衣 and 浴衣. If one extends this line of reasoning, then there’s no such thing as a set kun reading, and in the end it would seem that one can use any sort of reading one likes, as long as it’s not flat out wrong. Similarly, even following Ōgai’s method doesn’t solve the problem of whether or how much to use

okurigana, as in words like kuimono [food], deiri [movement], or ukeoi [contract]. Even if it did, we would be left with the problem of words like 寝台, for which the readings shindai or nedai [bed] are both legitimate. So in the end, there is no way to avoid the problem of multiple readings in written Japanese.

For this reason, I have given up on trying to use characters logically for certain readings, and recently am pursuing another method entirely. That is, to select them based entirely on the visual and musical effect they will produce in my writing. I look at ateji and kana usage entirely in terms of tone, and in terms of the beauty of the characters themselves, and attempt to use them in harmony with the sensibility of the work’s content.

To speak first of the visual effect, asagao [morning glory] has two different ateji, 朝顔 and 牽牛花, but I use the former when I want a Japanese, soft effect, and the latter to create a more Chinese, hard effect. The holiday tanabata is usually written 七夕 or 棚機, but if one were writing a story about China one could just as well use the characters 乞巧奠. Today we write the ateji for ranbō [violent] and josainai [tactful] as 乱暴 and 如才ない respectively, but in the Sengoku Era they were written 濫妨 and 如在ない, so in writing a historical novel this is the usage I follow. I follow the same principle in my use of kana, employing extensive okurigana when I want a passage to be clear, or pruning the okurigana when I am more concerned with achieving a particular tone. For this reason sometimes furumai [behavior] becomes 振舞, and sometimes 振る舞い. For example, in Shiga Naoya’s “

At Kinosaki,” ateji like 其処で, 丁度, 或朝の事, and 仕舞った are used, but when he wants to give the text a more gentle feel, like kana writing, nothing stops him from writing そこで, ちょうど, 或る朝のこと, and しまった.

...However, [these orthographic decisions] are made based on how they harmonize with the work’s content, and I make no allowance whatsoever to the reader’s needs. Once one starts to worry about whether every reader will read a word properly, there is no end to it, so I simply leave it all up to the reader’s literary understanding. As I see it, a reader who lacks that sensibility or common sense wouldn’t grasp the substance of the work anyway.

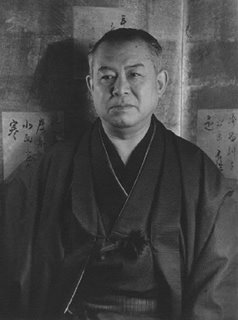

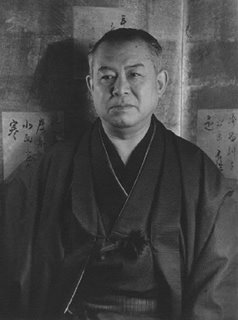

From Tanizaki Jun'ichirō, Bunshō tokuhon (1934).

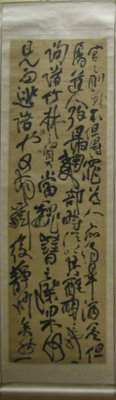

Over the weekend I visited the Met to see their new exhibit on Chinese calligraphy. It is a subject about which I wish I were less ignorant. Near the end of the exhibit (right before several pieces by Xu Bing), is a large and extremely eye-catching piece by the writer and intellectual Fu Shan (1607-1685). I’ve photographed a section of it for you to see. His most famous theoretical writing on calligraphy is an epilogue attached to a poem dedicated to his children. In it, he describes how his own technique was “ruined” by attempts to imitate the Yuan calligrapher Zhao Mengfu, instead of following the old masters of the Jin and Tang eras. He then continues:

Over the weekend I visited the Met to see their new exhibit on Chinese calligraphy. It is a subject about which I wish I were less ignorant. Near the end of the exhibit (right before several pieces by Xu Bing), is a large and extremely eye-catching piece by the writer and intellectual Fu Shan (1607-1685). I’ve photographed a section of it for you to see. His most famous theoretical writing on calligraphy is an epilogue attached to a poem dedicated to his children. In it, he describes how his own technique was “ruined” by attempts to imitate the Yuan calligrapher Zhao Mengfu, instead of following the old masters of the Jin and Tang eras. He then continues: